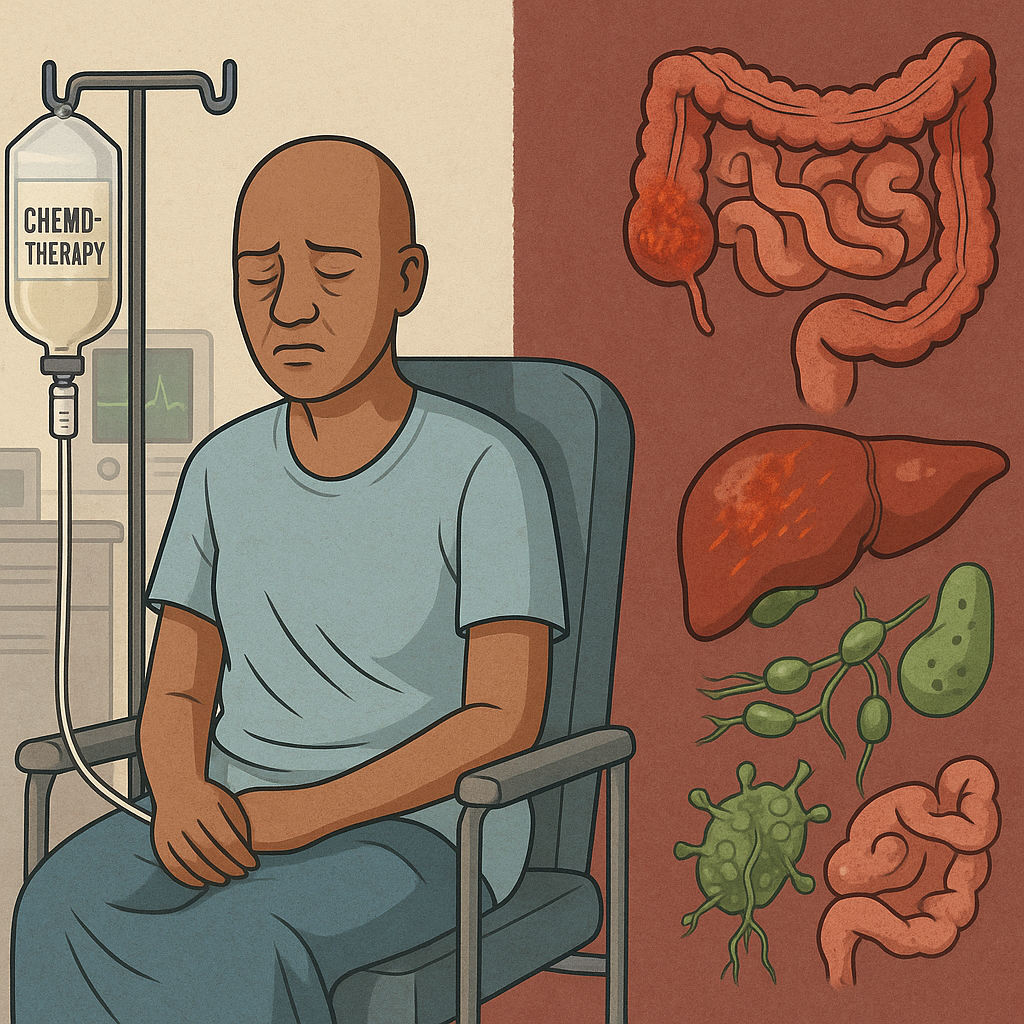

Conventional cancer therapies like chemotherapy, radiation, and corticosteroids are often essential for survival.

Nonetheless, they can deeply disrupt the body’s internal “terrain”. These therapies affect the very systems that support immunity, detoxification, and healing.

Below, we look into how these treatments can suppress the immune system. They can damage the gut and liver. These treatments also increase oxidative stress and impair the lymphatic system. This can undermine long-term recovery. We also examine how such terrain breakdowns contribute to cancer relapse. They lead to treatment resistance. We also discuss the added challenges and opportunities in global and African contexts.

Immune System Suppression by Chemo and Radiation

Conventional treatments frequently cause profound immune suppression, wiping out protective white blood cells:

- Chemotherapy’s lymphocyte depletion: Most chemo regimens sharply reduce lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, NK cells) during treatment. In breast cancer patients, lymphocyte counts drop significantly after chemo. Even 9 months later, key immune cells often remain below baseline. [1] to only ~60–70% of pre-chemo levels [2]. This lingering immunodeficiency leaves survivors vulnerable to infections long after therapy ends.

- Radiation-induced lymphopenia: Radiation therapy similarly triggers a substantial drop in circulating lymphocytes, since lymphocytes are extremely radiosensitive [3] [4]. Severe radiation-induced lymphopenia (RIL) occurs in an estimated 30–50% of patients, especially when large fields (e.g. chest or abdominal) are treated [5]. Notably, persistent lymphopenia correlates with worse cancer outcomes. Meta-analyses show RIL is linked to higher rates of tumor progression. It is also associated with lower survival [6] [7]. In short, these therapies erode the immune army. They particularly target NK cells and T cells that normally surveil and kill cancer cells. They create an immunosuppressed terrain. This terrain struggles to keep residual cancer in check.

- Steroids and immune suppression: Many cancer patients receive corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone or prednisone) to reduce swelling or nausea. Steroids are potent immunosuppressants that suppress multiple immune components, inhibiting T cell activation and reducing circulating lymphocytes [8]. While helpful for short-term symptom control, high-dose or long-term steroid use further dampens the body’s defense system. This compounds chemo’s immune-depleting effects.

Destruction of Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier

The gut is another “terrain” casualty of aggressive cancer treatment. Chemotherapy and radiation often damage the gastrointestinal lining and disrupt the gut microbiome, with cascading impacts on immunity and inflammation:

- Microbiome dysbiosis: Chemotherapy is well documented to unbalance gut flora. It wipes out beneficial microbes and allows opportunistic pathogens to bloom [9]. Studies show common chemo drugs have a strong effect on commensal bacteria. They dramatically reduce Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which are important for digestion and immune modulation. These drugs also increase harmful species such as Clostridium difficile [10]. In one clinical example, children on high-dose methotrexate showed a significant loss of Bifidobacterium in their gut. They also showed a significant loss of Lactobacillus when compared to healthy kids [11]. This dysbiosis not only impairs digestion but also lowers “colonization resistance,” making the patient more prone to infections by pathogens. Indeed, chemo-induced microbiome disruption has been linked to poorer treatment outcomes and higher toxicity rates [12].

- Mucositis and leaky gut: Cancer therapies often attack the fast-dividing cells of the intestinal lining. This can cause mucositis, which is painful inflammation and ulceration of the mucous membranes. This condition affects an estimated 40–100% of patients on aggressive chemo [13]. As the gut barrier breaks down, patients suffer nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain and malabsorption [14]. Even worse, a damaged intestinal barrier can become “leaky,” allowing bacteria and toxins to translocate into the bloodstream. Research confirms that treatment-induced mucosal barrier disruption leads to a massive pro-inflammatory immune response. It causes bacterial translocation. This sometimes causes bloodstream infections (bacteremia) [15]. For example, experiments with cyclophosphamide (a common chemo drug) found gut barrier damage and live bacteria migrating to lymph nodes and spleen [16]. In essence, chemo and radiation turn the gut into collateral damage – eroding the microbiome and gut lining that are pivotal for nutrient absorption, immune training, and infection prevention. Patients are left with a gut terrain marked by inflammation, “leaky” intestines, and altered nutrient metabolism [17].

Liver Overload and Reduced Detoxification Capacity

The liver, our main detox organ, works overtime during cancer treatment to metabolize drugs and filter toxins. Conventional therapies can overwhelm and even injure the liver, undermining its detoxifying capacity:

- Chemo-induced hepatotoxicity: Many chemotherapy agents are inherently toxic to liver cells (hepatocytes). As these drugs pass through the liver, they can overwork the organ to the point that it is “less able to do its jobs”[18]. In some cases, chemo directly damages hepatocytes or the small blood vessels in the liver. It’s well documented that certain regimens trigger conditions like sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, fatty liver (steatosis), or even “pseudocirrhosis,” which mimic severe liver disease [19]. These conditions can present with signs of acute hepatitis or liver failure in patients [20]. For example, survivors of colorectal cancer chemotherapy have been found to develop chemotherapy-associated steatohepatitis and fibrosis in the liver. Such damage not only threatens immediate health but also limits how much treatment a patient can tolerate.

- Impaired detox pathways: Paradoxically, chemo drugs can impair the very liver enzymes needed to break them down. The liver’s detoxification of many chemo agents relies on specific enzyme pathways (like cytochrome P450, UGTs, etc.), but if the drug itself injures liver cells, those pathways slow [21]. One hepatology review noted that chemo-induced liver dysfunction can alter enzyme activity and even cause cholestasis (poor bile excretion), leading to buildup of toxins [22]. In short, the liver’s capacity to filter blood, metabolize medications, and eliminate waste is compromised. Patients experience elevated liver enzymes, fatigue, jaundice, or other signs of liver stresss [23]. Over the long term, a liver that has faced intensive chemo/radiation may become less efficient. It might struggle to clear daily toxins. This inefficiency could allow more oxidative stress and inflammation in the body.

Heightened Oxidative Stress and Chronic Inflammation

A less visible but crucial aspect of terrain disruption is the surge in oxidative stress and inflammation provoked by cancer treatments. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy work in part by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill cancer cells – but those ROS also damage healthy cells and create lasting oxidative stress in the body:

- Tissue damage and ROS: Therapies like platinum-based chemo and radiation cause widespread cellular injury via free radicals. This often triggers a lingering “oxidative debt” in survivors. For instance, researchers studying childhood leukemia survivors years after chemo found significantly higher levels of ROS and oxidized glutathione in their blood than in controls, indicating an enduring redox imbalancer [24] The same survivors had elevated inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17), even long after treatment [25]. These findings suggest that chemotherapy produces a long-lasting alteration of redox status and chronic inflammation in the body [26]. In practical terms, a patient who finishes therapy may be cancer-free but left in a state of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress akin to accelerated aging. This inflammatory milieu can manifest as persistent fatigue, aches, cognitive “fog,” and increased vulnerability to chronic diseases.

- Inflammation fueling cancer’s return: Chronic inflammation is not only a side-effect – it’s also a known driver of cancer aggressiveness. In fact, tumor-associated inflammation is considered a hallmark of cancer progression. Inflammatory mediators like IL-6 and TNF can promote cancer cell survival, DNA damage, and immune escape. As one review summarized, persistent inflammation can affect almost every stage of cancer. It fosters metastasis. It stimulates cancer stem cells. It induces drug resistance. Finally, it aids cancer recurrence [27]. Thus, the pro-inflammatory terrain left by intensive treatment might unwittingly create fertile soil for any remaining cancer seeds to sprout. For example, if surgery or chemo doesn’t eliminate every malignant cell, chronic inflammation is all around. Oxidative stress could help those cells adapt. This stress can cause them to proliferate again. This is a cruel irony. The very treatments aimed at eradicating cancer can impair immunity. They can leave inflamed tissues and cause DNA damage. These conditions favor cancer’s resurgence or the emergence of new tumors years later.

Lymphatic Damage and Lymphatic Immune Disruption

Conventional cancer care often involves physical disruption of the lymphatic system – through surgical lymph node removal or high-dose radiation to lymph-rich regions. The lymphatic system is crucial for maintaining fluid balance and mounting immune responses. Its impairment can lead to lymphedema and immune dysfunction:

- Lymph node removal: Surgeries for cancers (breast, gynecologic, melanoma, etc.) commonly take out regional lymph nodes to check for spread. Unfortunately, lymph node dissection can permanently damage lymph flow, causing lymph fluid to accumulate in the limb – a condition known as lymphedema. Survivors with lymphedema suffer chronic swelling, fibrosis, and risk of infections in the affected arm or leg. Importantly, research shows that lymphadenectomy (node removal) can compromise adaptive immunity. It may impair the body’s ability to generate immune responses and antibodies in that region [28]. In breast cancer, for example, women who had many axillary nodes removed often have weaker immune surveillance in that arm [29]. While the overall immune system remains functional, the localized immune defenses are weakened. This weakness is why even a small cut on a lymphedematous limb can flare into serious infection.

- Radiation and lymphatics: Radiation therapy directed at lymph node areas (e.g. axilla, groin, neck) can scar lymphatic vessels and exacerbate lymphedema. Furthermore, radiation may destroy remaining lymph node tissue, reducing the immune cell hubs in those regions. Patients with secondary lymphedema often exhibit chronic inflammation in the swollen limb and impaired immune cell function [30]. In fact, lymphedema is now understood as an inflammatory disease itself. The stagnant fluid triggers cytokine release. It attracts immune cells that cause fibrosis. This adds yet another layer of terrain challenge. The immune system is suppressed globally by chemo. It is also dysregulated locally by lymphatic damage. The net result can be a survivor who is prone to cellulitis (skin infections). They have pain or mobility issues from swollen limbs. They lack the full immunological arsenal. As a result, they cannot respond to new threats or to microscopic cancer cells in that area.

Terrain Breakdowns Contributing to Relapse and Treatment Failure

The breakdown of the body’s terrain by conventional therapies is not just a quality-of-life issue – it has real implications for cancer control. Growing evidence links these treatment-induced changes to higher risks of cancer relapse, metastasis, and even resistance to further therapy:

- Loss of immune surveillance: A competent immune system is one of the body’s best weapons against residual disease. When treatments cause prolonged lymphopenia or NK cell depletion, any cancer cells left behind have an easier time evading detection and growing. For example, studies have shown that depleting NK cells (while leaving T cells intact) leads to worse control of metastases in experimental models [31]. Underscoring that NK cells are key to preventing spread. Clinically, patients who fail to regain normal lymphocyte counts after therapy tend to have higher recurrence rates. In essence, if the “guards” (immune cells) are knocked out, cancers can reemerge or migrate unchecked.

- Dysbiosis and treatment resistance: The gut microbiome is emerging as a surprising player in cancer outcomes. A healthy microbiota can modulate inflammation and even influence how tumors respond to therapy. Conversely, chemo-induced dysbiosis may contribute to treatment failure. Studies indicate that patients with disrupted microbiomes often have poorer responses to chemotherapy and more side effects [32]. Some gut bacteria produce metabolites. These metabolites help activate certain chemo drugs and keep the immune system alert. If those bacteria are wiped out, the therapy might be less effective at killing cancer cells. Additionally, a leaky and inflamed gut releases endotoxins. These endotoxins can keep the body in a chronic inflammatory state. As noted, this can nurture cancer persistence.

- Oxidative stress, inflammation and mutagenesis: The chronic inflammation and ROS overload left by treatment can drive genomic instability. This instability essentially sows the seeds for either the original cancer to recur. Alternatively, a new cancer might develop. Inflammation creates growth factors that help any surviving tumor cells thrive and can induce an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that makes cancer cells more invasive and drug-resistant [33]. Furthermore, oxidative DNA damage in healthy cells could lead to second malignancies years later. Cancer relapse or metastasis is more likely in a body that is inflamed and immunosuppressed, as the literature increasingly suggests. This is one reason why oncologists now pay attention to metrics like the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (an inflammation marker) or post-treatment lymphocyte counts as prognostic indicators.

- Therapy resistance: Ironically, very aggressive chemotherapy can select for chemo-resistant cancer cell clones. When the body’s terrain is strong, immune cells might eliminate those resistant stragglers. But if immunity is shot and tissues are inflamed, those hardy cancer cells can survive and even adapt (through inflammatory signaling) to resist future treatment. Chronic inflammation has been shown to promote cancer stem-like cells and drug resistance pathways [34]. This means that a patient with a broken-down terrain might not respond well to second-line treatments. A patient in this condition may also not respond to new lines of therapy. This is because the cancer has evolved in a hostile, inflamed environment. Ironically, this makes it tougher. In sum, the collateral damage from treatment includes weakened immunity and a dysbiotic gut. It also results in a toxic liver and inflamed tissues. These factors can create a perfect storm. They make a comeback of cancer more feasible and the body less equipped to suppress it.

Long-Term Decline in Survivors’ Health and Quality of Life

Surviving cancer is a blessing, but for many it comes at the cost of long-term health issues directly tied to the terrain damage we’ve described. Some of the enduring challenges include:

- Infections and secondary cancers: Because of immune suppression (and, in some cases, removal of immune organs like lymph nodes or spleen), survivors may face recurring infections. A simple flu or skin infection can hit harder. More gravely, impaired immune surveillance raises the risk of second cancers later in life, since the body is less efficient at catching rogue cells early. Epidemiological studies do show higher incidence of second primary tumors among those heavily treated with chemo-radiation, partly attributed to treatment side effects (mutation) and partly to weakened immunity.

- Gastrointestinal and nutritional problems: Damage to gut mucosa and microbiota can translate into chronic digestive issues. Many survivors report long-term changes in bowel habits, irritable bowel syndrome, or food intolerances after treatment. If the gut never fully heals its microbiome, they might have difficulty absorbing nutrients, leading to deficiencies or unintentional weight loss/gain. This can diminish energy and overall vitality. The loss of beneficial microbes can also affect mental health (the gut-brain axis), potentially contributing to anxiety or depressive symptoms post-treatment.

- Liver and metabolic health: A liver that has been taxed by chemotherapy might develop chronic conditions (fatty liver, fibrosis). Years after remission, some survivors show elevated liver enzymes or signs of liver strain. A reduced detox capacity means they may be more sensitive to environmental toxins or medications (for instance, a survivor might not tolerate a common drug dose that a person with an unscathed liver would). This can influence long-term health and requires monitoring. Additionally, metabolic syndrome features (high cholesterol, insulin resistance) are seen in some cancer survivor groups – possibly linked to systemic inflammation and organ stress from treatment.

- Fatigue and “accelerated aging”: Oxidative stress and inflammation act like a speeding clock on the body. Cancer survivors often describe feeling older than their years. They experience chronic fatigue, muscle loss, neuropathy (nerve damage from certain chemo drugs), and cognitive decline. In fact, researchers have found that inflammation remains elevated in survivors even 20 years post-chemotherapy, and higher inflammation correlates with worse cognitive performance (so-called “chemobrain”) [35]. For instance, a study demonstrated that breast cancer survivors showed significantly higher inflammatory markers. This was observed approximately 20 years after treatment compared to age-matched controls. Those with the highest inflammation also scored lowest on memory/attention tests [36] [37]. This suggests the toll of treatment can manifest as long-term brain fog and memory issues, reducing quality of life. Survivors also face increased risks of heart disease and frailty, thought to be driven by chronic inflammation and oxidative damage [38].

- Lymphedema and physical limitations: Survivors who developed lymphedema or had radical surgeries might deal with daily swelling, pain, and reduced mobility. Lymphedema in an arm or leg can make exercise or manual work difficult. It requires lifelong management such as compression garments and massage. These are resources that many patients struggle to access. Unmanaged lymphedema frequently leads to recurrent infections and hospitalizations, further burdening long-term health. Even aside from frank lymphedema, surgeries and radiation cause scarring and fibrosis that can restrict movement (for example, fibrosis in the chest after breast cancer can limit shoulder motion). These physical after-effects prevent survivors from returning to their prior fitness levels. Their independence and mental well-being are impacted.

- Emotional and psychosocial strain: A terrain disrupted by treatment can also affect one’s emotional resilience. Chronic inflammation has been linked to depression and anxiety. On top of that, the experience of serious illness and the residual side effects (like cognitive issues or sexual dysfunction from hormonal therapies) can weigh on survivors’ mental health. Many report that the survivorship phase – living with the after-effects – is as challenging as the treatment phase. This challenge is especially felt if they feel abandoned by the healthcare system once active treatment ends. Quality of life studies in African and global survivor populations confirm that persistent problems are common in the months and years after treatment. Fatigue, pain, and emotional distress are frequent issues. These factors underscore the need for ongoing support.

Terrain Challenges in African Contexts and Low-Resource Settings

Across the world, cancer survivors face terrain-related challenges, but these can be amplified in low-resource settings, including many parts of Africa. Systemic gaps often leave patients without support to recover their terrain, and cultural practices influence how patients cope:

- Limited survivorship care: In many African countries, formal survivorship programs are only just emerging. These programs, which address diet, rehabilitation, or psychosocial care after cancer treatment, remain scarce [39]. The healthcare focus is often on acute treatment. Once chemotherapy or surgery is done, patients may be discharged with minimal follow-up. This follow-up typically consists of periodic tumor scans. Support for gut, liver, immune or lymphatic recovery is generally not integrated into standard oncology practice. For example, a rural Kenyan or Ugandan patient returning home after chemotherapy is unlikely to receive guidance on rebalancing their gut microbiome or exercises to improve lymphatic flow. This lack of structured after-care means survivors often have to fend for themselves in managing long-term side effects. Many cannot afford specialized services like physiotherapy for lymphedema or dieticians for nutrition advice, and those services may not even exist in their vicinity.

- Reliance on traditional healers: In African communities, when the formal system doesn’t fill the gap, patients commonly turn to traditional medicine and faith-based healing for support. Traditional healers may provide herbs or concoctions aimed at “cleansing” the body after chemo, or spiritual rituals for strength. Surveys show that complementary medicine use is high among African cancer patients [40] [41]. In some cases, patients mix herbal remedies with their hospital treatments – though often without their doctor’s knowledge [42]. Traditional healers have long played a role in managing chronic illness; encouragingly, some healers now co-operate with medical providers to help with side effect management and palliative care [43] [44]. For example, a healer might give herbal infusions to alleviate chemo-related pain or help detox “heat” from the body. These practitioners are trusted in their communities, and when a survivor feels debilitated after aggressive chemotherapy, they may seek a healer’s help to restore balance. However, the terrain-focused care from traditional healers can be a double-edged sword: On one hand, it addresses cultural and holistic aspects. These include dietary herbs, massage, and spiritual counseling that biomedicine might ignore. On the other hand, there is a risk of unproven remedies or even harmful interactions.

- Case example – a clash of approaches: Consider a middle-class patient in Nairobi who, before starting chemo, fortifies herself with a nutrient-rich diet, probiotics, and immune-boosting herbal teas – a personal “terrain-focused” regimen learned from online support groups. Once chemo begins, however, she is hit with strong steroids, multiple chemo drugs, and antibiotics for an infection. Unsurprisingly, she experiences severe gut issues and fatigue. These symptoms erase the gains of her prior wellness efforts. She feels frustrated that the treatment that may save her life is simultaneously “undermining her from within.” In rural settings, we hear of patients who initially avoided hospital therapy, trying months of herbal treatment to strengthen the body (the belief being that cancer is a whole-body imbalance). When they finally undergo late-stage chemotherapy out of necessity, they often describe it as two steps forward, one step back. The cancer might shrink, but they are left physically wrecked. They lose faith in both the herbs and the chemo. These narratives highlight a common blind spot in conventional cancer care: the lack of integration with supportive therapies that could preserve or rebuild the body’s terrain during treatment.

- Lack of resources for recovery: Financial and infrastructure constraints in Africa exacerbate terrain issues. For example, lymphedema sleeves or pumps to manage swelling are expensive and not widely available; a breast cancer survivor in Ghana or Nigeria may simply live with a swollen arm, as physiotherapy clinics are few. Similarly, probiotics or supplements that some Western survivors use to help gut and liver recovery are often out of reach for African patients (either unavailable locally or too costly). Nutritional support may consist of general advice at best – there is seldom provision of specific diets or fermented foods for microbiome health. Moreover, basic needs like clean water, a balanced diet, and sunlight exposure can be challenging for patients in impoverished areas, further hindering recovery. These factors result in more severe and longer-lasting terrain damage for African survivors. This worsens their post-cancer quality of life, as documented in many sub-Saharan survivor studies [45] [46].

Despite these challenges, there are efforts underway to bridge the gap. Cancer support organizations in countries like Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria are increasingly aware of the need for holistic survivorship care, including counseling, nutrition, and management of late side effects. The African Palliative Care Association and other groups are training healthcare workers to address not just the tumor, but the “whole patient” – body and mind – especially after active treatment ends.

Integrative and Terrain-Aware Approaches for Healing

A compassionate, constructive way forward is to combine conventional cancer treatment with “terrain-aware” supportive care – helping patients maintain or restore their internal balance during and after therapy. This is not about being “anti-doctor” (doctors aim to cure the cancer, which is paramount), but about expanding the toolset to protect the patient’s long-term health while the cancer is attacked. Integrative oncology approaches around the world (including some pioneering African centers) are showing promising strategies:

- Probiotics and fermented foods: Because of the gut microbiome’s importance, probiotic supplementation is being used to mitigate chemo’s collateral damage. Clinical trials have found that probiotics can reduce treatment-related diarrhea and intestinal inflammation, improving patients’ comfort and nutritional status [47] [48]. In fact, multi-strain probiotics have been shown to help regenerate the gut lining (promoting regrowth of intestinal villi) and maintain microbiome diversity during chemo-radiotherapy [49]. Cancer centers now often recommend yogurt, kefir, or fermented foods during recovery. These foods include sauerkraut and kimchi. They are natural probiotics that can gently reintroduce beneficial bacteria. In African contexts, traditional fermented foods exist. Examples include sour porridge, kefir-like drinks, or fermented cassava. These foods could serve a similar role in diet. By healing the gut and preventing dysbiosis, we not only reduce short-term side effects but potentially improve treatment outcomes (some studies suggest patients with a healthier microbiome respond better to certain therapies).

- Nutritional and herbal detox support: To assist the liver, plant-based and herbal remedies can be used. These remedies support overall detoxification alongside medical care. Milk thistle is rich in silymarin. It’s a well-known example and an antioxidant herb used traditionally to support liver function. Early research indicates it might protect liver cells during chemo [50] [51]. Similarly, turmeric (curcumin) has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Some trials are examining if it can reduce radiation-induced inflammation or chemo side effects. It is important to use high-dose supplements with medical guidance to avoid interference with treatment. African medicinal plants are valued for their potential health benefits. Survivors often use plants like moringa, ginger, or bitter leaf to “clean the blood.” They are also used to help regain strength. These plants have rich antioxidant profiles. They could indeed help quench residual free radicals in the body. A balanced diet abundant in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains is universally encouraged. It provides essential vitamins like A, C, and E. The diet also supplies phytonutrients needed to combat oxidative stress. Importantly, such diets also feed the good gut bacteria with fiber. Many oncologists now work with nutritionists. This collaboration helps patients finish treatment with a personalized diet plan. These plans focus on liver-friendly and gut-friendly foods. This is a growing area in African oncology units. Local fruit and vegetable staples could be integrated into post-therapy care. Herbs could also be included.

- Movement and lymphatic therapy: Exercise and physical therapy are emerging as powerful tools for survivor health. Even gentle exercise (walking, yoga, tai chi) can stimulate the lymphatic circulation and reduce inflammation. Studies have found that cancer survivors who engage in regular physical activity experience less fatigue. They have lower markers of inflammation. There is also a possibility of improved survival rates. In the context of lymphatic damage, lymphedema massage and compression can greatly improve quality of life. Terrain-aware care would ensure early referral to a lymphatic therapist for a patient who had lymph nodes removed. Patients are taught how to do self-massage. They are also given compression garments to prevent severe lymphedema. In Africa, some creative solutions are being tried. Patient support groups teach each other low-cost lymph massage techniques. They also use locally made wraps for compression. Movement also helps detoxification: deep breathing and muscle activity assist the lymphatics and blood flow in clearing metabolites. Furthermore, weight-bearing exercise can counteract the loss of bone density that sometimes follows chemo or steroid use. The key is a tailored exercise program that respects a survivor’s limits but gradually rebuilds strength.

- Sunlight and nature therapy: Adequate sunlight exposure is crucial for vitamin D synthesis, which supports immune function and bone health. Many cancer patients have vitamin D deficiency, and correcting this has been associated with better outcomes in some studies. Terrain-aware healing encourages survivors to get safe sun (e.g. morning sun) and spend time in nature. Sunlight and fresh air can improve mood and regulate circadian rhythms disrupted by chemo (hospital schedules often disturb sleep-wake cycles). In African contexts, sunlight is abundant; the challenge is more about awareness – incorporating outdoor activity as part of recovery. Some survivor groups organize nature walks or gardening activities, which provide gentle exercise, sun, and psychological uplift all in one.

- Emotional and spiritual support: Healing the terrain is not only physical. Emotional care – counseling, support groups, stress management, faith or spiritual practices – can significantly affect biological outcomes. Chronic stress and depression are linked to higher inflammation and poorer immune function in survivors [52] [53]. By providing psychosocial support, we can lower stress hormones and possibly reduce those inflammatory signals. Integrative programs often teach relaxation techniques. These may include meditation, breathing exercises, prayer, or music therapy. These techniques help patients find calm and meaning. In turn, this may strengthen their immune response. In Africa, integrating traditional practices – like prayer groups, storytelling, or communal gatherings – can tap into cultural strengths. For example, some hospitals have introduced patient cancer support groups. These groups are led by survivors or nurses. In them, people can share experiences and coping strategies. This camaraderie reduces fear. Feeling not being alone can improve adherence to healthy behaviors. As a result, this enhances the internal terrain. As one survivor in Nigeria put it, “I needed healing for my soul after the chemotherapy broke my body. The support group was my medicine for that.” Such testimony echoes across cultures: care that addresses mental and spiritual health ultimately reflects in better physical resilience.

In summary, terrain-aware care is about filling the blind spots of standard oncology. It asks: who is caring for the patient’s whole well-being while the oncologist fights the tumor? By bringing in nutritionists, physiotherapists, naturopathic supports, and psycho-social experts into the cancer team, we create a more balanced approach. This is especially crucial in lower-resource settings where patients can easily fall through the cracks post-treatment. Simple interventions – a probiotic supplement, a daily walk in the sun, an herbal tea for liver support, a listening ear from a counselor – can make a world of difference in how a survivor rebuilds.

Conclusion: Toward Integrative, Terrain-Focused Cancer Care

Conventional treatments save lives, but they should not stop at defeating the tumor. The next step is healing the terrain that the cancer – and the treatment – ravaged. As we’ve seen, chemotherapy, radiation, and other drugs can leave patients immunosuppressed, inflamed, and depleted, setting the stage for possible relapse or long-term health decline. This is a system-level oversight in modern oncology: focusing so intently on the cancer that the patient’s broader physiologic health is sidelined. It is possible to be pro-cure and pro-healing – to attack the cancer while actively supporting the patient’s internal environment.

Adopting a terrain-focused lens means viewing the patient holistically. It means oncologists working hand-in-hand with supportive care providers (nutritionists, physiotherapists, psycho-oncologists, traditional medicine practitioners where appropriate) to ensure that when a patient finishes treatment, they are not left as a “wrecked house” in which cancer easily returns, but rather as a rebuilt, resilient home for a healthy life. The compassionate goal is to improve not just survival, but thriving after survival.

Such integrative approaches are gradually gaining traction worldwide. In Africa, where resource constraints and cultural dynamics play a big role, innovative hybrid models are needed – for instance, training traditional healers to collaborate with hospitals on managing side effects [54], or community health workers following up with survivors to implement diet and exercise plans. Globally, research is focusing more on interventions such as diet modification and gut flora restoration. Efforts are also directed towards anti-inflammatory therapies and mind-body programs in cancer aftercare. Early evidence is promising. These interventions can reduce relapse rates. They can also enhance quality of life. However, larger trials and systemic support are needed.

Ultimately, supporting the body’s terrain is an act of empowerment and compassion. It’s recognizing that a cancer patient is not just a collection of malignant cells to eliminate, but a whole person who will hopefully live for years or decades after the last chemotherapy drip. We preserve immune function. We protect the gut and liver. We calm inflammation, and we mend the lymphatic system. Through these actions, we fortify that person for the road ahead. In doing so, we honor not only the goal of curing disease, but also the equally important goal of promoting long-term healing. This vision aims to both conquer cancer. It also focuses on rejuvenating the patient, providing a better path to truly defeating cancer’s grip on our lives and societies.

Sources:

- Fred Hutch News – Chemotherapy weakens immunity for months [I] [II]

- Front. Oncol. 2024 – Radiation-induced lymphopenia and survival [III] [IV]

- OUP Oncology – Corticosteroids’ immunosuppressive effects [V]

- Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021 – Chemo, microbiota dysbiosis & mucositis [VI] [VII]

- Cancers 2021 – Chemo disrupts gut flora & barrier, causes translocation [VIII] [IX]

- Saint Luke’s Health – Chemo can overwork and harm the liver [X]

- Ann. Hepatol. – Chemo impairs liver enzyme detox pathways [XI]

- Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2014 – Chemo can cause SOS, steatosis, cirrhosis-like damage [XII]

- Research (ALL survivors) – Long-lasting oxidative stress & inflammation after chemo [XIII] [XIV]

- Front. Pharmacol. 2022 – Chronic inflammation -> metastasis, drug resistance, recurrence [XV]

- Front. Immunol. 2019 – Lymph node removal -> lymphedema, impaired immune responses [XVI]

- PubMed (NK cells study) – NK cell depletion worsens survival and metastatic control [XVII]

- Ecancer review – Chemo-induced microbiome disruption linked to poor outcomes [XVIII]

- Breast Cancer Res. 2019 – 20-year survivors have higher inflammation & cognitive decline [XIX]

- Arch. Public Health 2023 – Traditional healers co-manage side effects, see patients after failed hospital treatment [XX] [XXI]

- ResearchGate (ASCO) – Survivorship programs are needed in Africa [XXII]

- MDPI Cancers 2021 – Probiotics reverse intestinal damage from chemo, reduce diarrhea [XXIII] [XXIV]

✅ Ready to Support Your Terrain During or After Treatment?

Conventional therapies may fight the tumor. However, your terrain needs support to recover fully. Your gut, liver, lymph, and immune system are important.

🌿 I offer practical, food-based healing guidance that works with your body — not against it. Whether you’re in treatment, remission, or seeking clarity…

📲 Tap the button below to chat with me directly or send a message here.

Let’s personalize your healing plan.

Discover more from Mike Ndegwa | Natural Health Guide

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.