Surviving cancer is not the end of the healing journey. It’s the start of a new chapter. This chapter focuses on rebuilding and restoring the body’s “internal terrain.” Conventional follow-up care often emphasizes surveillance for recurrence. It focuses on managing acute side-effects. Still, it often overlooks proactive rehabilitation of the survivor’s overall health [1] [2].

Many survivors recall only generic lifestyle advice given briefly at the start of treatment. There is little integration into survivorship care [3]. This leaves a gap, especially in lower-resource settings, where formal survivorship programs are scarce [4] [5]. The result is that critical aspects of recovery are often neglected in conventional plans. These include gut health, detoxification, immunity, and psycho-spiritual well-being. Yet evidence shows that addressing these areas can reduce relapse risk. It can also improve quality of life.

Additionally, these measures promote immune reconstitution [6] [7]. In Africa and other regions, survivors often turn to nature-based practices. They also adopt lifestyle-driven methods, sometimes born of cultural wisdom or necessity. These help them regain strength. These strategies include fermented foods and faith-based healing. They are not alternatives to medical treatment. They represent the vital next step after it. They help the survivor become an active participant in their healing. This is true whether they are still in therapy. It applies when they are in remission or even decades into survivorship.

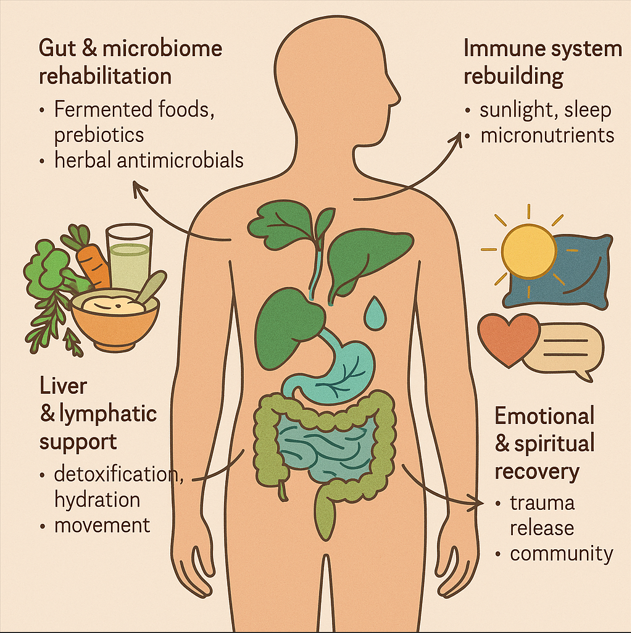

Below, we explore the four pillars of internal terrain restoration after cancer:

- The first is gut and microbiome rehabilitation.

- The second is liver and lymphatic support.

- The third is immune system rebuilding.

- The last is emotional and spiritual recovery.

Healing the Gut and Microbiome

Harvesting baobab fruit in Limpopo, South Africa – a nutrient-rich fruit that is often fermented. Fermenting African fruits like baobab increases their protein and fiber content. It also introduces probiotics. These changes contribute to better metabolic health [8].

Cancer treatments vs. gut health: Chemotherapy and radiation often ravage the gut’s delicate ecosystem. Research confirms that anticancer chemotherapy can significantly affect the microbiota structure. It disrupts beneficial flora and hampers its recovery. This can have serious long-term consequences [9] [10]. This post-chemo dysbiosis manifest as persistent inflammation, digestive issues, weakened immunity, and even mood changes (via the gut-brain axis). Rebuilding a healthy microbiome is thus a cornerstone of post-cancer recovery.

Fermented foods and probiotics: One of the safest and most accessible ways to restore gut balance is through diet [11]. Fermented foods – rich in live cultures, enzymes, and acids – can reseed and nourish the gut microbiome. In fact, fermented foods have been shown to significantly increase microbial diversity and reduce inflammatory markers in the body [12]. This is especially relevant to cancer survivors, as chronic inflammation and loss of microbial diversity are linked to poorer outcomes. A 2021 study on melanoma patients showed that a high-fiber diet supports gut bacteria. Patients on this diet had improved progression-free survival when on immunotherapy [13]. Notably, fermented foods outperformed high-fiber alone in boosting microbiome diversity and dampening inflammation [14]. The benefits of fermented foods are multifold. They introduce beneficial bacteria (such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species). Additionally, they increase bioavailability of nutrients and produce bioactive metabolites. Finally, they help crowd out pathogens [15] [16].

Global and African fermented staples: Fermented foods are found in virtually every culinary tradition. These include yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha. In Africa, a rich heritage of fermented staples provides natural probiotics and nutrients. For example, injera is the spongy sourdough flatbread of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It is made from fermented teff grain. This flatbread teems with gut-friendly microbes [17] [18]. In West Africa, they consume ogi (also called pap). It is a fermented cereal pudding made from maize or millet. It is commonly eaten in Nigeria [19]. In East Africa, uji is a tangy fermented porridge of millet or sorghum, often enjoyed in Kenya and Tanzania [20]. Many African communities also ferment dairy. For example, mabisi/amasi is a fermented milk in Southern Africa. In Nigeria’s Fulani culture, they ferment nunu [21]. These traditional foods are inherently nutritious (being made from whole grains, tubers, and milk). Fermentation enriches them further. It packs them with beneficial bacteria and B-vitamins [22] [23]. Tambra Stevenson, an African nutrition expert, explains that African fermented foods have been a cornerstone of our diets for centuries. They serve not just as nourishment but as a vital part of our cultural identity. These foods also play a role in our community practices. They are packed with beneficial bacteria. These nutrients support gut health. This support is increasingly recognized as essential for overall well-being, Stevenson notes [24] [25]. From Kenyan uji to Nigerian ogi. Ghanaian nkatenkwan (fermented corn dough) and Sudanese kisimor (sorghum ferment) are also popular. These foods help rehabilitate the gut ecosystem naturally.

Prebiotics and fiber: Alongside fermented foods, cancer survivors are encouraged to eat plenty of prebiotic-rich fiber. These include vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and legumes. They fuel the growth of healthy gut bacteria. Fiber intake aids in bowel regularity. This is crucial after treatments like opioids or surgery that can slow GI motility. It also produces short-chain fatty acids. These acids heal the gut lining and modulate immunity. High-fiber diets have been correlated with better treatment responses and survival in some cancer contexts [26]. One study noted that dietary fiber >30g/day was beneficial for patients on immunotherapy [27]. Even simple additions like ground flaxseed or psyllium can act as gentle prebiotics. Many African plant foods are excellent sources of fiber and prebiotics – e.g. cassava, yam and plantain (often eaten fermented as in gari or fufu), leafy greens like amaranth, and local fruits. Notably, African fermented root foods like cassava and yam improve markers of renal health. They also enhance the glycemic response. This underlines that fermentation can enhance not just gut flora but systemic metabolism [28].

Herbal antimicrobials: After intensive treatments, survivors often face overgrowth of undesirable microbes. Frequent antibiotic use for infections can exacerbate this issue. These microbes include Candida (yeast) or pathogenic bacteria. Nature offers a toolbox of gentle antimicrobials that can help “reset” the microbiome without the harsh effects of pharmaceuticals. For example, garlic (Allium sativum) is a time-honored remedy in Africa and worldwide for infections. It holds sulfur compounds (like allicin) with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and also acts as a prebiotic. Garlic has demonstrated broad antimicrobial effects and immunomodulatory benefits in research [29]. It can selectively inhibit harmful microbes while sparing beneficial ones, and also stimulate immune cells to action. A 2015 review noted that garlic appears to enhance the functioning of the immune system. It stimulates certain cell types, including macrophages, lymphocytes, and natural killer cells. [30] [31]. In practical terms, survivors include raw or fermented garlic in their diet. They also use garlic-based herbal supplements under professional guidance. Other herbal antimicrobials popular in integrative care include oregano oil and thyme. Also, it includes berberine-containing herbs, such as Berberis species or the African herb Zanthoxylum chalybeum. Additionally, neem (also known as Azadirachta indica, used in East Africa) is included. These all have traditional uses for gut infections. These can help combat dysbiosis or “bad bugs” without wrecking the microbiome. It’s worth noting that many African traditional medicinal plants used for stomach ailments (e.g. African ginger (Siphonochilus aethiopicus), Egyptian black cumin (Nigella sativa), or ‘dawadawa’ ferments like Parkia biglobosa) likely exert part of their benefit by modulating gut bacteria.

Scientific outcomes: Rebuilding the gut terrain is not just about comfort; it may influence cancer outcomes. Gut microbes help regulate inflammation and train the immune system – key factors in keeping cancer at bay. Studies have shown that certain gut bacteria can improve responses to immunotherapy and even chemotherapy [32] [33]. Conversely, persistent dysbiosis is linked to higher inflammation (e.g. elevated IL-6, CRP) which can create a pro-cancer environment [34]. By restoring microbial balance through fermented foods, fibers, and herbs, survivors may reduce chronic inflammation and strengthen their immune surveillance. Epidemiological evidence shows that fermented food consumption is tied to general health benefits. For example, higher yogurt or kimchi intake is associated with reduced all-cause mortality. It also leads to metabolic improvements and a lower risk of diseases like diabetes [35]. This is all relevant to a survivor’s long-term well-being. All these data underscore that nurturing one’s inner microbial garden after cancer is not “alternative” folklore. It is a scientifically sound strategy to improve quality of life. It also reduce relapse risk.

Importantly, these gut-healing practices are accessible and affordable. In many African settings, survivors not afford fancy probiotics. However, traditional fermented foods (prepared at home) and local herbs are readily available. What’s more, these align with cultural dietary patterns, making adoption easier. Embracing the fermented porridges, sour breads, and probiotic beverages of one’s heritage can be a way to reclaim health. In a Nigerian focus group, one survivor expressed their belief in traditional healers. They stated that herbs, including garlic and ginger, can cure cancer. [36]. While “cure” may be a strong word, the sentiment shows a faith in nature’s healing power. It restores internal balance. By rehabilitating the gut microbiome, survivors lay a strong foundation for recovery. Gut health is truly the gateway to overall health.

Supporting the Liver and Lymphatic System

If the gut is the body’s microbial garden, the liver and lymphatic system are its sanitation and detox departments. Cancer treatments (chemotherapy drugs, anesthesia from surgeries, pain medications, etc.) can leave a heavy toxic residue and strain on the liver. Radiation and immunotherapies generate cellular debris that the lymphatic system must clear. A comprehensive recovery, therefore, pays special attention to gentle detoxification and drainage to reset the body’s internal environment.

The liver – our chemical processor: The liver metabolizes most chemotherapy agents and is often hit with collateral damage. Hepatotoxicity (liver inflammation or elevated enzymes) is common during chemo. Even after treatment, survivors may have lingering liver stress or fatty changes. Herbs known as “hepatoprotective” or “bitter tonics” can be immensely helpful in this phase. Bitters stimulate bile flow, aiding digestion and the elimination of waste and toxins. A classic example is milk thistle (Silybum marianum) – widely used in integrative oncology to help the liver recover. Milk thistle’s active compound silymarin has been shown to reduce chemotherapy-induced liver inflammation in clinical trials [37] [38A]. A placebo-controlled study in children on leukemia treatment observed trends. It found trends toward improved liver enzymes with milk thistle supplementation [38B]. Similarly, milk thistle is associated with histological improvements in liver tissue. It is also explored as a preventative measure against liver damage [39] [40]. While milk thistle is Mediterranean in origin, many African survivors have adopted it as an available supplement. It illustrates the broader principle: support the liver’s natural detox pathways rather than letting toxins linger.

African bitter herbs and greens: Africa has a rich pharmacopoeia of bitter herbs. These herbs have traditionally been used as general health tonics. They are often used post-illness. One standout is Bitter Leaf (Vernonia amygdalina), a shrub common in West, East, and Central Africa. Bitter leaf is consumed as a leafy vegetable in soups. It requires some soaking to reduce its bitterness. It is also taken medicinally for maladies. These include illnesses like malaria, diabetes, and gut issues. It is known in various local names. These include Ewuro (Yoruba, Nigeria), Onugbu (Igbo, Nigeria), Mululuza (Luganda, Uganda), Olusia (Luo, Kenya), and Ndolé (Cameroon) [41]. True to its name, every part of the plant is intensely bitter due to bioactive compounds (lactones, alkaloids, etc.). These compounds have demonstrated significant health effects – including anti-inflammatory, liver-protective, and even anticancer properties. Lab studies show that aqueous extracts of V. amygdalina can kill cancer cells and enhance the efficacy of chemo drugs in mice [42]. In one study, adding bitter leaf extract to chemotherapy improved treatment outcomes in a breast cancer model [43]. Human clinical data are still limited. However, using bitter leaf as a daily soup or tea is widespread in parts of Africa. Many people use it in survivorship. It gently detoxifies by stimulating bile. It also acts as a diuretic. Additionally, it provides vitamins (A, E, C) and antioxidants. Another African bitter is African wormwood (Artemisia afra). It is used in Southern Africa under the Zulu name: Umhlonyane. It is famous for its anti-malarial properties. It is also employed to “clean the blood.” Moringa oleifera (drumstick tree) is less bitter but contains bitter components in its leaves. It is a nutrient powerhouse often given to convalescents. It supports liver enzymes and also reduces inflammation. In South Africa, an herbal remedy called Cancer Bush (Sutherlandia frutescens) is traditionally given to cancer patients after treatment. It serves as an adaptogen and liver tonic. It’s bitter and thought to boost the body’s resilience. These examples highlight how local botanicals can effectively support survivorship care. They aid in detoxification and organ support in a cost-effective manner.

Bitter Leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) in bloom. This African shrub (known as Ewuro, Onugbu, etc. locally) is used as a post-illness tonic. Its bitter compounds support digestion and liver health. Studies indicate it can induce apoptosis in cancer cells. It may even improve chemotherapy’s efficacy in animal models [44].

Detoxification strategies: Beyond herbs, survivors can adopt simple “detox” strategies in daily life. Hydration is paramount – drinking ample clean water and herbal teas helps the kidneys and lymph flush out wastes. You can gently stimulate the liver by adding a squeeze of lemon to warm water in the morning. The sourness triggers bile flow. Many cultures promote periodic cleansing diets after illness. This includes African traditional medicine. These diets might include light foods like porridge and green leafy vegetables. They also suggest plenty of fluids. This is done to give the liver a rest from heavy processing. Fiber (as discussed in gut health) also aids detox by binding toxins and excess hormones in the gut. These toxins and hormones then can be excreted. A diet rich in fruits and veggies acts like a broom for the system. Sweating therapies can support detox: whether through exercise, or traditional sweat baths/saunas common in some African cultures, inducing sweat helps eliminate certain toxins and relieve burden on the liver. In East Africa, for example, some communities use herbal steam baths (often with neem leaves, eucalyptus, or other herbs) to help patients recover from fever and “remove impurities” – a practice that could likewise help a chemo-weakened body.

Lymphatic support: The lymphatic system is often overlooked, yet it’s critical in recovery. It is essentially the body’s drainage network, clearing cellular debris, carrying immune cells, and maintaining fluid balance. Surgery or radiation can damage lymph nodes and vessels (for instance, breast cancer survivors may have lymph node removal leading to lymphedema risk in the arm). To support lymphatic circulation, movement is key. Unlike blood, lymph fluid has no central pump – it moves only when we move (muscle contractions and deep breathing push it along). Survivors should be encouraged to do gentle exercise as able: walking, stretching, yoga, light rebounding (mini-trampoline) are excellent lymph movers. Even deep diaphragmatic breathing is shown to enhance lymph flow through the thoracic duct

[45] [46]. Research on breast cancer survivors shows that exercise (including water exercise and dance) can reduce lymphedema risk and improve fatigue [47] [48]. One small study found that aquatic therapy combined with deep breathing significantly sped up lymph drainage in post-mastectomy patients [49]. In African contexts, survivors might engage in communal dance or traditional physical labor. These activities, like gardening, serve as their form of exercise. The rhythmic movements can serve a lymphatic massage function. Manual therapies are another pillar: lymphatic drainage massage, if available, can help reduce swelling and detoxify tissues. In lower-resource areas, even simple self-massage or using compression wraps on affected limbs can assist.

In addition, certain herbs support lymphatic function – for example, red root (Chaparral) and cleavers (Galium aparine) are used in Western herbalism for lymph, and Africa has its analogs like “Uganda green tea” (Justicia or Gymnanthemum spp.) used for blood cleansing. Adequate hydration again is vital – lymph fluid is mostly water, so dehydration can make lymph sluggish. Survivors should aim for at least 8 cups of fluid a day (more if physically active or in hot climates). In practical terms, an African survivor may incorporate habits like starting each morning with a cup of warm herbal tea (e.g. moringa or lemongrass) to hydrate and stimulate lymph flow.

Scientific evidence and outcomes: Supporting the liver and lymphatic system is somewhat harder to quantify. It is more difficult than, say, measuring a blood cell count. But proxies exist. One indicator of a successful “internal terrain” restoration is reduction in markers of chronic inflammation and oxidative stress. The liver plays a role in controlling systemic inflammation (through acute phase reactants, etc.), and a well-functioning liver can modulate these better. Some studies have measured improvements in quality of life when using detoxifying approaches. For example, cancer patients were given liver-supportive supplements. These included a mix of antioxidants and herbs. They reported better appetite and less fatigue [50]. In integrative oncology practice, naturopathic physicians often recommend garlic as part of a post-treatment protocol. It helps to support liver metabolism. It also prevents cancer recurrence [51]. Garlic’s sulfur compounds can enhance Phase II liver detox pathways and also thin the blood, which is particularly useful for survivors on hormonal therapies that raise clot risk (e.g. Tamoxifen) [52]. Another clinical angle is the management of “chemo brain” or cognitive fog. Poor liver clearance of chemo metabolites might contribute to this fog. Improving liver function could potentially alleviate cognitive symptoms faster. However, more research is needed. On the lymph side, studies clearly show that exercise is tied to better survivor outcomes. It not only lowers lymphedema, but also reduces the risk of cancer recurrence and mortality. Regular physical activity after cancer reduces the risk of cancer-specific death by 50–60%. This is seen in diseases like breast and colon cancer [53] [54]. While this is partly due to weight management and metabolic effects, improved immune surveillance via lymphatic circulation could also play a role. It boosts lymphatic function. This may be one contributing mechanism.

In low-resource settings, where high-tech interventions are limited, these nature-based strategies (bitter herbs, hydration, movement) are pragmatic and empowering. They allow survivors to actively participate in their recovery using available resources. As one Kenyan cancer survivor described, “I did not have money for special medications after chemo. So, I went back to my roots – literally. I drank bitter leaf soup and aloe vera. I walked every morning. I followed what my grandmother would say to do after an illness. It cleansed me.” (Personal testimony from a survivor recounted to an ethnobotanical researcher [55]). Such testimonies echo across communities. Survivors feel “lighter” and regain their appetite. They see their skin and eyes clear up after embracing liver- and lymph-supportive practices. While anecdotal, they align with the biological understanding that a cleaner internal terrain fortifies the body against cancer’s return.

Rebuilding Immune Strength and Vitality

Cancer and its treatments can leave the immune system in a state of disarray. White blood cell counts may be low. Immune memory may be weak. Surveillance against rogue cells may be impaired. Rejuvenating the immune system is thus a critical goal in survivorship. Unlike a drug that targets a specific molecule, immune recovery takes a holistic approach. It involves nutritional repletion, restoration of circadian rhythms, stress reduction, and gradual conditioning of the body. The good news is that the immune system has remarkable capacity to regenerate under the right conditions. Survivors can actively foster those conditions through lifestyle.

Sunrise over the Serengeti in East Africa – symbolic of the healing power of natural sunlight and circadian rhythms. Regular sun exposure helps the body produce vitamin D, a crucial immune-supportive hormone. In breast cancer survivors, higher vitamin D levels post-diagnosis were associated with about 30% better survival outcomes compared to deficient levels [56].

Sunlight and circadian alignment: Sunlight is a natural immune booster. UVB rays on the skin drive the production of vitamin D, a hormone that profoundly influences immune function (e.g. enhancing T-cell activity and NK cell cytotoxicity). Multiple studies link higher vitamin D status with improved cancer survival [57] [58]. For instance, a large study in breast cancer survivors found that those with vitamin D levels in the sufficient range had a significantly lower risk of recurrence and death. There was about a 30% improvement in survival [59]. Vitamin D insufficiency is common, even in sunny climates, due to indoor lifestyles or skin covering. Survivors are encouraged to get sensible sun exposure – about 15-20 minutes to arms and legs, mid-morning or late afternoon, most days – to naturally raise vitamin D (especially important if supplements are unaffordable or unavailable). Besides vitamin D, morning sunlight synchronizes the circadian clock, which regulates immune cell cycles and stress hormones. A stable circadian rhythm (sleeping at night, active in daytime) promotes better immune regulation. In fact, disrupted circadian rhythm and poor sleep have been associated with higher inflammation and even greater cancer progression in some studies. Therefore, prioritizing good sleep hygiene is an immune-strengthening strategy. Survivors should aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep nightly [60] [61]. Simple steps include keeping a consistent sleep schedule, sleeping in darkness, and managing pain or hot flashes that interfere with rest (through medication or natural remedies). In African households that may be busy or crowded, this can be challenging; creative solutions like short daytime naps or use of eye masks/earplugs can help.

Nutrition and micronutrients: After cancer treatment, many survivors are malnourished or have micronutrient deficiencies (zinc, vitamin C, B12, iron, etc.) that can hamper immune recovery. A nutrient-dense diet is fundamental. This means emphasizing whole foods: plenty of fruits (for vitamins and antioxidants), vegetables (for vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals), adequate protein (to rebuild tissues and immune cells), and healthy fats (for cell membranes). Research shows that cancer survivors who eat a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and beans have better overall survival. They experience a lower recurrence in some cancers [62] [63]. In one observational study, colon cancer survivors adhering to a “prudent” diet (high in plant foods and fish) had significantly lower recurrence rates than those on a “Western” diet high in red meat, fat, and sugar [64]. The American Cancer Society and World Cancer Research Fund recommend survivors follow similar guidelines as for cancer prevention: “Eat a diet rich in whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and beans” and limit processed and red meats [64] [65]. These plant foods are packed with micronutrients that the immune system needs. For example, citrus fruits and guava (common in Africa) provide vitamin C to support leukocyte function; green leafy veggies and beans provide folate needed for DNA repair; nuts and seeds give zinc and vitamin E which aid immune cell response. Traditional African diets – when based on ancestral foods – tend to excel in these aspects: dishes like bean stews, leafy soups (e.g. Nigerian egusi soup with vegetables), maize and millet porridges, and tropical fruits form an immune-friendly plate. It’s when Westernized processed foods take over that nutrient density falls. Thus, a survivorship plan should encourage returning to wholesome, preferably locally-sourced foods.

Specific micronutrients worth highlighting include: Vitamin D (discussed above; if sun is insufficient, supplements or fortified foods should be considered), Zinc (found in legumes, seeds, and meats; supports skin and gut immunity and lymphocyte production), Selenium (a mineral important for antioxidant enzymes, found in sorghum, millet, and Brazil nuts – though not native to Africa, many soils have selenium-rich plants), and iron/B12 (to correct anemia and ensure vigorous oxygenation of tissues; can be obtained from meats or leafy greens for iron, and animal foods or fortified foods for B12). If blood tests show deficiencies, targeted supplementation might be needed; however, even without testing, a safe approach is a regular multivitamin or moringa leaf powder (often called the “vitamin tree,” moringa leaves are rich in A, C, calcium, iron, etc.) to fill gaps. In one Kenyan cancer center, nutritionists started providing moringa and millet porridge to survivors who couldn’t afford commercial supplements, with reported improvements in energy levels.

Physical activity and fitness: Exercise is repeatedly proven to be one of the most powerful lifestyle medicines for survivors. Beyond aiding lymphatic circulation (as noted) and detox, exercise directly benefits the immune system by reducing inflammation and stimulating anti-cancer immune activity. Regular moderate exercise (e.g. brisk walking 30 minutes a day) has been shown to increase the proportion of cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells in circulation, and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Clinically, cancer survivors who stay active have lower rates of recurrence and longer survival across multiple cancer types [66] [67]. For example, breast cancer patients who engaged in ~3-5 hours of moderate exercise per week had a 40-50% lower risk of death than sedentary patients in observational studies [68]. Similar trends are seen in colon cancer. Exercise also dramatically improves quality of life – it reduces fatigue (ironically, moving more can increase energy), alleviates anxiety, and improves sleep [69]. Even issues like “chemo brain” may improve with the increased blood flow and neurochemical benefits of exercise. The American Cancer Society recommends survivors “be physically active in everyday life – walk more, sit less,” aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise a week [70]. In practice, survivors can start small and adapt to their capacity: short walks that gradually lengthen, gentle yoga or stretching, or even resuming farm or household tasks as tolerated. Many African survivors return to agricultural work – tending a garden or field – which can double as exercise and a source of organic produce for their diet. Culturally relevant activities like dancing (as in communal celebrations or church) are wonderful as well – providing a workout and joy simultaneously. The key is consistency and listening to one’s body, increasing activity as strength returns.

Stress modulation: Chronic stress suppresses immune function, whereas a calm mind supports it. The cancer experience is traumatic – uncertainty, fear of recurrence, financial stress, all can keep survivors in “fight or flight” mode. This leads to elevated cortisol and adrenaline, which over time weaken immune defenses (reducing lymphocyte counts and natural killer cell activity). Thus, finding ways to dial down stress and cultivate inner peace is literally immunotherapy of its own kind. Techniques like meditation, deep breathing, mindfulness, or prayer can help activate the parasympathetic “rest and heal” response. Studies have found that mindfulness meditation programs for cancer survivors result in lower levels of stress hormones and improved immune parameters [71] [72]. Even simple breathing exercises – for example, the 4-7-8 breathing technique or pranayama from yoga – practiced for a few minutes a day can reduce anxiety and induce relaxation. In Africa, many survivors turn to faith and spirituality as a source of stress relief and hope (more on that in the next section). Engaging in prayer or attending religious services often provides solace and can physiologically lower stress through communal support and the act of surrendering fears to a higher power. Spending time in nature is another underrated healer – just sitting under a tree or walking in the bush can calm the nervous system and provide gentle exercise and sun at the same time. Traditional lifestyles inherently included such nature exposure, which modern urban life often lacks. A return to nature, even if just gardening or walking outside at sunrise, can be deeply restorative.

Immune-rebuilding in context: In many African countries, advanced medical immune therapies (like post-transplant growth factors or expensive immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs) are inaccessible. But nature’s immune boosters are available to all: sun, sleep, nutrition, exercise, and stress reduction cost little or nothing. For example, in Uganda, a survivorship program encouraged survivors to form walking groups in the early morning sun, combining exercise, sunlight, and social connection at once – an approach that any community could implement. These women reported not only feeling physically stronger but also less depressed. Objectively, those who consistently participated had fewer infections and hospital visits in the subsequent year (as per an informal report by the program organizers). Science supports what they experienced: holistic lifestyle changes create a bodily environment hostile to cancer. One analysis notes that engaging in healthy behaviors can counter some adverse effects of treatment and improve overall outcomes in survivors [73] [74]. Indeed, lifestyle interventions (nutrition, weight control, physical activity) are now recognized as “important aspects of survivorship care” because cohort studies suggest they positively impact disease-specific outcomes [75].

In summary, rebuilding the immune system after cancer is about building vitality. It requires tending to basic pillars of health consistently. As the body recovers its immune footing, survivors often notice tangible signs: more energy, fewer colds/infections, faster wound healing, and an overall sense of resilience. These are affirmations that they are not merely “living with” a past of cancer, but thriving beyond it, with an internal terrain that is once again vibrant and responsive. And importantly, by taking these actions, the survivor regains a sense of control and partnership in their health – no longer a passive patient, but an active healer.

Emotional and Spiritual Recovery

The end of cancer treatment does not mean the end of cancer’s emotional impact. Many survivors carry deep psychological scars: trauma from the diagnosis and treatment, fear of recurrence looming over daily life, altered body image from surgeries, grief for the loss of “normalcy,” and sometimes a spiritual crisis of meaning. Emotional and spiritual healing is therefore an essential – yet often under-addressed – component of post-cancer recovery. Attending to this realm not only improves quality of life but can have physical health benefits too (since mental health and immunity are intertwined). As a 2025 study in Ghana concluded, “the need is to cater not only to bodily but also to emotional, social and spiritual needs that arise in the lives of cancer patients” [76]. This holistic view aligns with many African traditional perspectives, where illness is seen as affecting body, mind, and spirit collectively, and healing is only complete when all are addressed.

Processing trauma: Up to 1 in 5 cancer survivors develop clinical post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from their experience, and an even larger proportion have subclinical post-traumatic stress symptoms [77] [78]. Symptoms can include nightmares, flashbacks of treatment, anxiety with any health issue, and hyper-vigilance (“scanning” one’s body constantly for signs of cancer’s return). It’s crucial for survivors and healthcare providers to recognize this and not dismiss the psychological fallout. “Many cancer patients believe they need to adopt a ‘warrior mentality’ – stay positive and never seek help for emotional issues, seeing that as weakness,” observes Dr. Chan, a psycho-oncology researcher [79]. “There needs to be greater awareness that there is nothing wrong with getting help to manage the emotional upheaval – particularly depression, anxiety, and PTSD – post-cancer.”[80]. Normalizing mental health care is step one. Survivors should be encouraged to speak about their fears and feelings, whether to a professional therapist, an elder, a support group, or a trusted friend. Counseling and support groups can be immensely beneficial. In many African communities, formal psycho-oncology services are limited, but alternative avenues exist: church groups, patient-led survivor networks, or traditional healers who also serve as informal counselors. For instance, in Nigeria and Uganda, studies found that traditional healers often provide psychosocial support and spiritual counseling alongside herbs [81] [82]. In South Africa, a concept of the “cancer buddy” system (pairing survivors to talk and lend mutual support) has been introduced by NGO programs to help process trauma through shared experience.

Community and social support: “Ubuntu” – the African philosophy meaning “I am because we are” – underscores the healing power of community. Social isolation can be deadly; a study of breast cancer survivors showed that women who were socially isolated (few social ties) had significantly higher rates of recurrence and mortality than those who were socially integrated [83]. Conversely, strong social support is correlated with improved survival. Community support comes in many forms: practical help (family assisting with chores, cooking, so the survivor can rest), emotional encouragement, and the sense of not being alone in the journey. In African contexts, extended family and community often rally around the ill – though cancer’s stigma can sometimes interfere. Reducing stigma through education is important so that communities embrace survivors rather than shun them. The spiritual community is particularly salient: in Ghana, 93% of cancer patients in one study said they relied on spiritual beliefs to cope, and most felt that doctors and nurses should pay attention to patients’ spiritual concerns as part of care [84]. Many African survivors credit prayer circles, congregation visits, or the simple presence of faith leaders for keeping their spirits up. “My church group prayed with me every week. It gave me strength knowing they were fighting with me in spirit,” one survivor said. This sense of communal spiritual battle can alleviate the loneliness of survivorship.

Ancestral and cultural healing practices: Tapping into one’s cultural heritage can provide a framework for emotional healing. For example, some cultures have specific cleansing rituals after a serious illness – symbolically washing away the disease and marking a new beginning. Participating in such a ritual (with water, herbs, or smoke) can have profound psychological significance, signaling to the survivor’s psyche that they have crossed a threshold. Storytelling is another traditional method: African societies often use narrative to make sense of suffering. Survivors might be encouraged to share their story in a supportive setting – this can be cathartic and help transform the narrative from one of victimhood to one of survivorship and purpose. In fact, “survivor stories” are increasingly used in survivorship programs to inspire and also allow survivors to voice their journey, aiding emotional processing. Some may seek out ancestral guidance – for instance, consulting a traditional healer or engaging in ancestral rituals to ask for continued protection and health. While such practices may lie outside biomedical frameworks, they can imbue survivors with a sense of connection to lineage and existence beyond the self, which often brings comfort and meaning.

Faith and spirituality: Cancer often triggers existential questions: “Why did this happen to me?”, “What is the purpose of my life now?”, “What happens when I die?”. Engaging with those questions spiritually can be a path to emotional peace. Whether through religion (e.g. prayer, reading holy texts, participating in sacraments) or personal spirituality (meditation, connecting with nature, practicing forgiveness), survivors frequently report that faith is a source of hope and strength. Studies have found that greater spiritual well-being and religious coping are associated with improved quality of life and reduced distress in cancer patients [85]. In one cross-sectional study, cancer patients with higher spiritual well-being had less depression and more resilience [86] [87]. In Africa, where religiosity is generally high, leveraging this is key. Hospitals and clinics can integrate spiritual care – for example, having chaplains or traditional spiritual healers available. Even simple measures like providing a space for prayer or connecting patients with religious support resources can help. Many survivors mention that their faith gave them a sense of control – “I left it in God’s hands” – thus alleviating constant worry. However, it’s also important to address when spirituality induces guilt or conflict (e.g. “Did I get cancer because God punished me?” or facing pressure to appear faithful and positive at all times). Compassionate counseling can help reframe these thoughts (no, cancer is not a punishment; seeking help is not a lack of faith, etc.). Ultimately, spiritual recovery often means finding meaning: some survivors find new purpose (advocacy, volunteering, caring for others) as a way to make meaning of their survival. This existential healing can be the most profound, converting a traumatic experience into “post-traumatic growth” – a concept where individuals emerge with deeper appreciation of life, spiritual development, and a drive to help others.

Therapies for emotional healing: A variety of mind-body therapies have evidence in survivor populations. Yoga and Tai Chi, for instance, combine gentle physical activity with mindfulness and have been shown to reduce stress and improve sleep in cancer survivors [88]. They also help with flexibility and pain. Expressive arts therapy (using art, music, or dance to express emotions) can be very therapeutic; some African survivorship programs incorporate drumming circles or dancing, tapping into cultural modes of expression to release emotions. Massage therapy not only addresses physical tension but provides comforting human touch which many survivors crave after the clinical, sometimes isolating treatment period. In regions with traditional massage practices (like Ethiopian mich or West African shea butter massage), integrating those can both honor culture and soothe the survivor. Psychotherapy (individual or group) with a trained counselor can teach coping skills and cognitive techniques to manage fear of recurrence – for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can reframe catastrophic thoughts, and newer techniques like meaning-centered therapy focus on restoring a sense of purpose. In low-resource areas, structured therapy might be replaced by peer support groups, which have shown benefit in reducing anxiety and loneliness. The mere knowledge that someone else “gets it” can be healing.

The mind-body-immune loop: Addressing emotional and spiritual health isn’t just about feeling better mentally; it feeds back into physical health. Chronic stress and unresolved trauma can keep the body in an inflammatory state, whereas emotional relief and spiritual comfort can lower stress hormones and boost immune functioning. For example, a Kaiser Permanente study noted that socially isolated women had higher inflammation and worse outcomes [89]. On the flip side, interventions like mindfulness meditation have been found to increase NK cell activity in breast cancer survivors [90]. There is even research suggesting that forgiveness and social support correlate with favorable changes in immune markers in survivors [91]. This bi-directional communication means that the work a survivor does in therapy or in prayer isn’t “all in their head” – it resonates through their nervous and immune systems. A peaceful mind can translate to a body that is less hospitable to cancer. As one study succinctly put it, spirituality and religious coping were “consistently associated with improved quality of life, reduced distress, and in some cases better clinical outcomes”[92].

Cultural strengths in Africa: African communities have inherent strengths for facilitating emotional and spiritual healing. The sense of community (Ubuntu) means people don’t have to suffer alone – family and neighbors often rally (where stigma doesn’t impede). The respect for elders and wisdom means survivors may have guidance from those who have seen adversity and can counsel patience and hope. The integration of song, dance, and oral tradition provides outlets for expression and catharsis; for example, in some cultures, women’s support groups sing songs of struggle and victory, including about illnesses, turning pain into art. The prevalence of faith provides a framework for acceptance and hope (e.g. believing in divine plan or miracles). By leveraging these cultural assets, survivorship care in Africa can be both locally resonant and deeply effective. It’s notable that even without formal psychologists, many African survivors cope through what might be termed “ethnopsychology” – practices ingrained in culture that serve therapeutic roles. A qualitative study in Nigeria found that cancer patients frequently visited faith-based healers not just for cure, but for emotional support and meaning-making – they valued prayers and the notion of spiritual attack/defense as it gave a narrative to their illness [93] [94]. The same study reported patients calling for collaboration between doctors and traditional healers, recognizing that each addresses different needs (medical vs. spiritual) [95]. This suggests that holistic survivorship programs should consider collaboration with chaplains and respected community healers to cover all bases.

Empowerment and identity: Perhaps the capstone of emotional recovery is when a survivor moves from identifying as a “victim” of cancer to a “victor” or simply a person for whom cancer was a chapter, not the defining story. Empowerment comes from regaining a sense of agency. By actively engaging in gut healing, liver support, immune rebuilding, and emotional/spiritual practices as described, survivors often feel re-empowered: they are doing something positive for their health each day. This agency itself combats the helplessness that fuels anxiety and depression. It shifts the mindset from “I am waiting, hoping the cancer won’t come back” to “I am proactively building my health to keep cancer away.” When survivors realize their capacity to influence their well-being, it’s profoundly hopeful. They become, in essence, co-authors of their future health, not just passengers dreading fate. This psychological shift – from passive to active – is perhaps one of the most important outcomes of integrative survivorship care.

Survivor’s voice: To illustrate, consider the story of a Kenyan survivor of advanced lymphoma (as documented in an ethnographic study [96]): After remission, she was left with fatigue, numb hands and feet (neuropathy), and deep fear of relapse. Her oncologists had no specific follow-up beyond scans. Feeling adrift, she joined a local cancer survivors’ association. There she learned about dietary changes and was introduced to a traditional herbalist. She began eating fermented foods (sour porridge), taking a daily bitter aloe tonic, walking in the mornings, and attending a weekly prayer meeting with other survivors. “At first, I was skeptical,” she said. “But within months, I noticed changes – my energy came back, I could sleep without pills, the tingling in my feet reduced. More than anything, my spirit healed. I stopped seeing myself as sick. I started helping new patients, sharing my story. Cancer is not a death sentence, it was my awakening.” This testimonial encapsulates the empowering, hopeful tone that defines successful survivorship care beyond the hospital. It shows how restoring the internal terrain – physically and emotionally – can give survivors not just extra years of life, but life in those years.

Conclusion: Thriving as a Co-Architect of Healing

Life after cancer can be truly life renewed. By focusing on rebuilding the gut microbiome, supporting detox organs, strengthening the immune system, and healing emotionally and spiritually, survivors lay the groundwork for long-term wellness. These nature-based and lifestyle-driven paths, often long practiced in traditional cultures, complement modern medicine in a powerful way. They are essential whether a person is actively in treatment (helping to mitigate side effects), in remission (fortifying the body to prevent recurrence), or in long-term survival (maintaining health and vitality).

It is important to stress that these approaches are not presented as an alternative to standard oncology – rather, they are the vital next steps after medical treatment, addressing aspects of recovery that the medical model typically doesn’t. Conventional cancer care may win the war against the tumor, but rebuilding the “terrain” is how we win the peace that follows. By engaging in these practices, the survivor steps into a proactive role. They transition from being a patient (one who receives care) to a participant and co-architect of their own healing. This empowerment alone has healing power: it restores a sense of control and partnership with one’s body.

Globally, and especially in Africa, these integrative survivorship strategies have an added importance. In high-income settings, a cancer survivor might have access to rehabilitation programs, dietitians, counselors, and cutting-edge drugs. In lower-resource settings, those supports may be minimal or absent – but the traditional wisdom of fermented foods, bitter herbs, sun and activity, family and faith can fill much of that gap. They are low-cost, culturally accessible, and sustainable. The gap in formal follow-up care in many African countries [97] [98] makes it even more crucial to disseminate knowledge about these self-care practices. Fortunately, initiatives are underway (often led by survivor groups or NGOs) to incorporate nutrition, physical activity, and psychosocial support into survivorship plans in Africa [99] [100]. There is a recognition that improving survivorship is the next frontier of cancer control on the continent, where incidence is rising and more people are surviving [101] [102]. Culturally tailored programs – like community gardens for survivors, integration of traditional medicine with oncology clinics, and church-based health ministries – are bridging the old and new. They validate that modern medicine and ancestral wisdom can coexist for the patient’s benefit.

In closing, the journey of post-cancer restoration is one of hope and resilience. Scientific evidence now affirms what perhaps our grandmothers knew: that healing is a holistic process. A survivor who drinks a cup of probiotic-rich sorghum malt (such as Zimbabwe’s mahewu), who seasons their soup with garlic and bitter herbs, who stretches in the morning sun and joins friends in prayer or song – that survivor is engaging in profound medicine. They are treating the soil in which any remaining cancer cells might try to take root, making that soil inhospitable to disease and fertile for health. They are treating their whole self.

As survivors embrace these practices, many find that survivorship is not merely a return to the status quo, but an opportunity for personal transformation. Their bodies grow stronger, their minds calmer, their spirits richer. And with each passing day of clean eating, movement, and meaningful living, the specter of cancer fades further into the background. The empowered survivor stands at the center of this picture: not defined by cancer, but defined by how they reclaimed life afterwards. In the words of an inspiring saying often shared in survivor circles: “Cancer may have started the fight, but I finish it by how I live.” By restoring the body’s internal terrain, survivors aren’t just hoping to avoid relapse; they are actively cultivating a life of wellness. They demonstrate that life after cancer can be a time of thrivership – a time in which one heals at every level and truly lives well, with gratitude and purpose, every precious day going forward.

Discover more from Mike Ndegwa | Natural Health Guide

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.